|

Each year the MOHAI Youth Advisors work together on a culminating group project that they envision, plan, and create together. Last year, the 2022-23 MYA cohort designed and produced a coloring book that serves as a love letter to the history, places, people, and cultures of Seattle. Together they brainstormed and selected topics, drew and designed images, researched and wrote snapshot histories, and designed the look and feel of the book. We have a limited number of risograph copies beautifully printed and assembled by Paper Press Punch that will be distributed at MOHAI programs and to community partners for free! You can also print your own copy from the pdf below, formatted for 8.5 x 11” paper. Access the MOHAI Online Collection to view the historic photos that inspired the pages of this coloring book (and more!) via mohai.org/collections Share your colored pages with us on Instagram @mohaiteens!

0 Comments

By Justin L. Editor’s note: This piece was created during the 2023 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing.

In classic ask-for-forgiveness-not-permission mentality, this “Good Will Committee” of “leading Seattle citizens” took the towering pole to bring back to their city. [4] While one might expect physical violence or deceitful manipulation from such an event, none was reported by the expedition party. Just the audacity of showing up on strangers’ shores and treating their home like a souvenir shop. According to an account by third mate R. D. McGillvery, “the Indians were all away fishing, except for one who stayed in his house and looked scared to death. We picked out the best looking totem pole... we chopped it down - just like you'd chop down a tree. It was too big to roll down the beach, so we sawed it in two.” [3] In a lawsuit filed months later by the original owners of the totem pole, James Clise who was the ringleader and Acting President of the Commerce responded that “there were two decrepit Indians which we finally succeeded in interviewing, who made no objection to our taking the pole to Seattle.” [3]

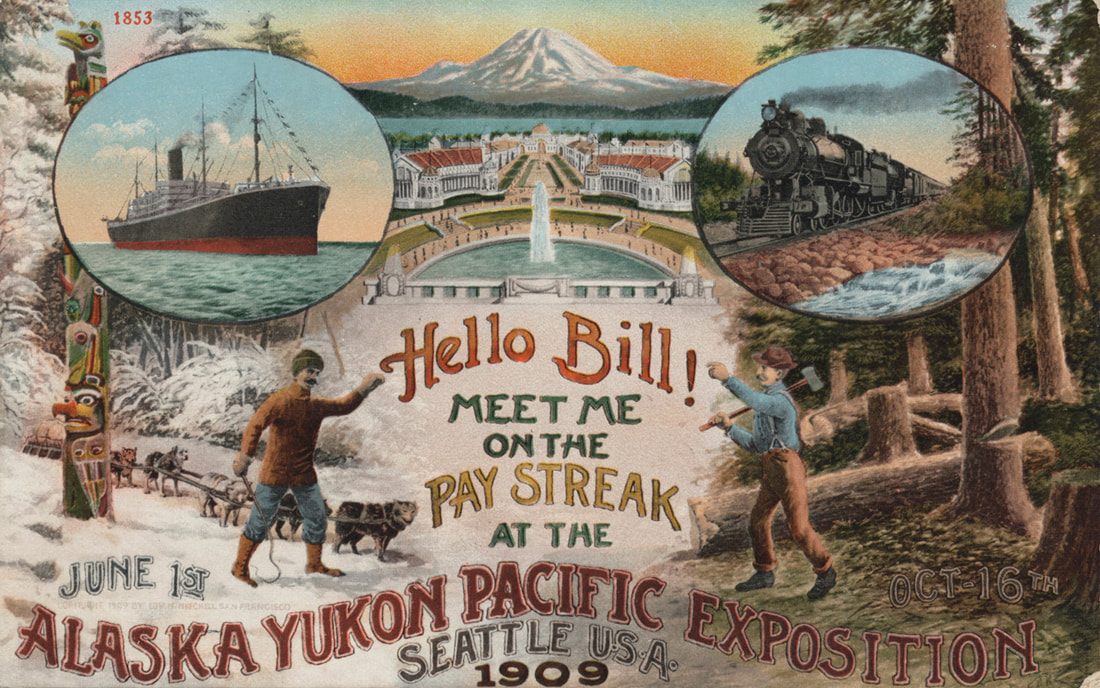

Attorney William H. Thompson, speaking on behalf of his eight defendants, justified the act saying that “here [in Seattle] the totem will voice the natives' deeds with surer speech than if lying prone on moss and fern on the shore of Tongass Island.” [3] To state this presumes that not only does Native culture belong to all Americans, but also that the preservation of Native culture requires the magnanimous aid of white people, who will truly appreciate and help elevate its worth. Both are untrue, but these beliefs were on full display at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (AYPE) of 1909, where the totem pole served as a poster child for the first world’s fair hosted in Seattle, the ‘City of Totems’.

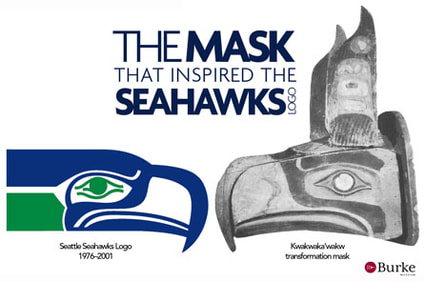

The fair positioned Seattle as a shining city on the edge of a vast American empire. In the face of unprecedented growth of the Seattle economy, those who were wistful for the pastoral past became fascinated with the wilderness, and romanticized it. This was an untapped market, Seattle noticed. Positioning Native people and culture at the fair as backwards, exotic, and mysterious helped communicate to fairgoers that Native land was their visit and take from, and Seattle was their Gateway to the North. It offered the adventure of a lifetime, and was the frontier to a spectacle. The ways Native people were on display at the fair, however, was not simply harmless fascination. It chipped away at Native sovereignty, and actually reflects hatred. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker, co-authors of “All The Real Indians Died Off” and 20 Other Myths About Native Americans, bust the myth that all “Native American Culture Belongs to all Americans.” They note that scholar Rayna Green is one of the first to use the concept “Playing Indian”, to unpack the ways in which Americans’ obsession with the “vanishing race'' at times “translated into trying to become them, or at least using them to project new images of themselves as they settled into North America.” [8] Seattlelites did not love Native culture. They pitied upon Native culture because compared with their industrialized standards of living, they saw Native people as noble savages stuck in the past. And by co-opting their culture and ‘ownership’ of the wilderness, they sought to replace them.

Footnotes:

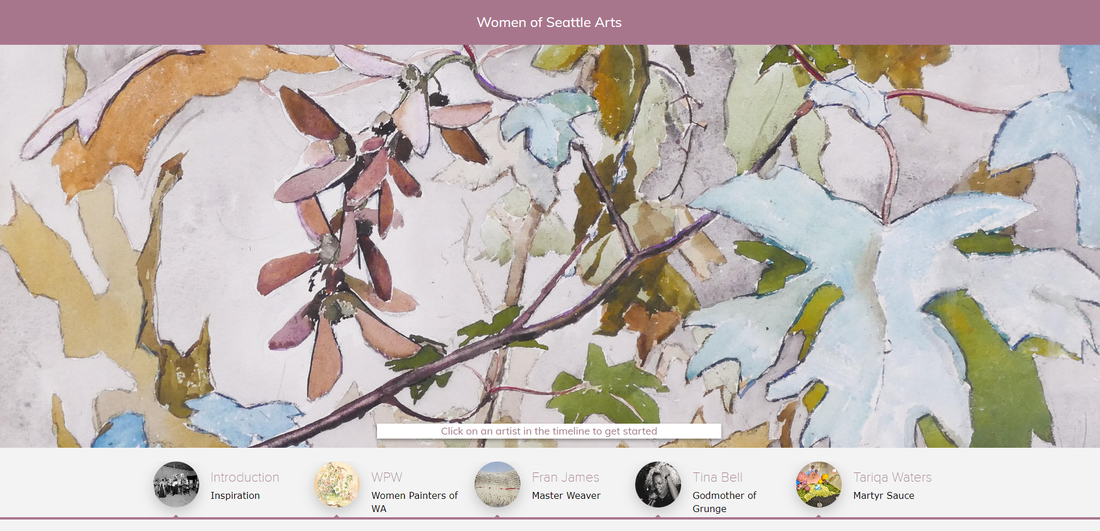

10/16/2023 0 Comments Interactive: Women of Seattle ArtsEditor’s note: This piece was created during the 2023 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing. For her project, Nora created a web interactive that spotlighted four different women artists/organizations from a variety of artistic disciplines and time periods. This year's History Lab was inspired by the Museum of History and Industry exhibit Celebrating Pacific Northwest Artists: 25 Years of the Neddy Awards. As a participant, I was prompted to incorporate Seattle art and artists into my research project. As someone who has lived just outside the city her whole life, I wanted to focus on the diverse types of art that have been produced by local artists. As I began research, I started to look up parts of Seattle’s art scene and lesser known stories of artists. The first one I found was Tina Bell. Bell’s story fascinated me as I found it so bizarre that someone who seems so influential could be so relatively obscure. That led me to focus on other women who have helped to shape Seattle’s art scene. Before this project I was oblivious to each of the women I chose to write about. I found it curious that I hadn’t heard of any of them when they all have a huge legacy in Seattle and the Pacific Northwest. Throughout this project I noticed similarities between all these women and how they’ve each been challenged with being underrepresented in their fields. I created this project in order to highlight and showcase their unique stories and accomplishments that so more people can learn about them. I hope that this helps to bring to light their talents and contributions to the arts.

- Nora

This series of Rainy Day History bonus episodes were designed to provide a soundtrack to your MOHAI experience and are best listened to as part of the playlist below. If you’re at the museum, we encourage you to pop in some headphones and listen to the introductions and curated songs while you walk through MOHAI’s core exhibit, True Northwest: The Seattle Journey.

In this playlist, MOHAI Youth Advisors Chelsea and Charlee will introduce three musical pairings hand-picked to complement your exploration of a specific section of True Northwest, then you will get a chance to listen to the songs. Join us on a musical journey through Seattle history! Show Notes:

Episode Transcripts:

Sources:

Explore more:

A podcast episode by Karly

Editor’s note: This piece was created during the 2022 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing.

What makes Seattle a great place to write and to write about? Learn about three writers past and present whose work has shaped and been shaped by the city.

Episode transcript

Bibliography Music: "Good Morning St. Martin" by Aldous Ichnite; Source: Free Music Archive, CC BY-NC license. Author Links: https://www.octaviabutler.com/ https://www.lindywest.net/ https://washuta.net/ About the podcast: Rainy Day History A webzine by Jasmine Z. Editor’s note: This piece was created during the 2022 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing. 11/4/2022 1 Comment Aki Kurose: A Life Remembered

By: Nathan D.

Editor’s note: This piece was created during the 2022 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing. Growing up in the Central District

After Pearl Harbor

At that time, Kurose was in her senior year at Garfield High School, and the next day she remembers a teacher saying to her, “Your people bombed Pearl Harbor.” As those words hit her, she suddenly became very aware of her “Japaneseness,” “not in a real positive way, but kind of a scary way,” she remembered. She no longer felt like an equal American anymore. [2]

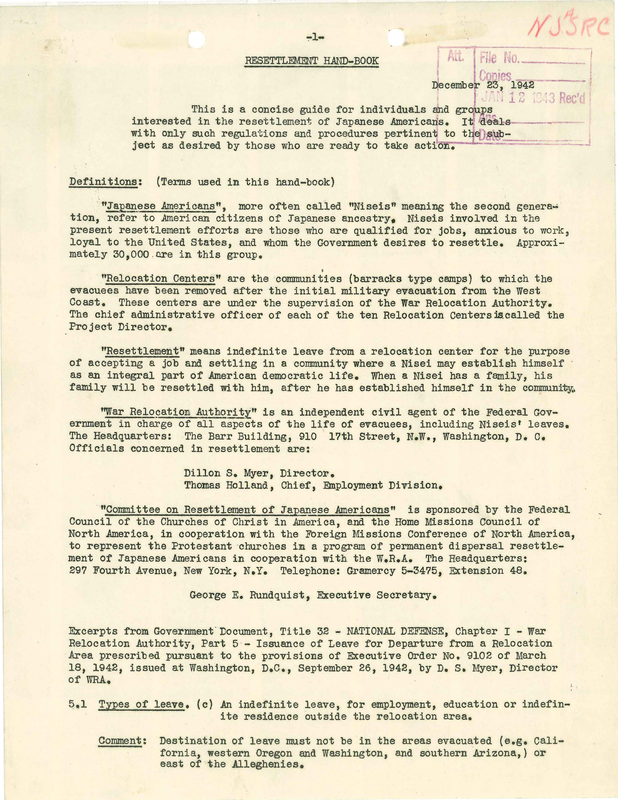

Months later, on February 19th. 1942. President Roosevelt wrote Executive Order 9066 which authorized the exclusion of “any and all persons” from living in established “military zones”. [3]This resulted in the forced removal of Japanese immigrants and Japanese American cities from their homes along the West Coast to incarceration centers monitored by the military. [4]

Aki’s entire family was first moved to the Puyallup Assembly Center (located on the Puyallup Fairgrounds, and called “Camp Harmony” by army officials), along with other Japanese Americans ranging from Western Washington to Alaska. The barracks and shower stalls at the detention facility were mostly communal. Aki, who was raised to be very modest and private, recalled this being “devastating”. [5] The temporary structures were poorly constructed; some were converted animal stalls, and they had no insulation. Aki also remembered, “they gave us army cots and then they gave us these bags and we were to stuff them [with hay] for mattresses…But my sister, Suma, was very asthmatic, so that was terrible. She could not survive with the straw mattresses, you know. And so she spent a lot of time in the hospital in camp, because of her asthma. And [the] medical care was not that adequate either.” [6] After a few months at Puyallup, her family was transferred to the “Minidoka Relocation Center,” in Idaho. The detention center wasn’t finished when incarcerees first arrived, but at least it seemed more stable than the barracks in Puyallup, Aki remembered. “This time they gave us army mattresses, so we didn't have to stuff mattresses when we went there. And there were still the steel army cots and we had to arrange the six beds so that there'd be space enough for us to move around. And then there was the mess hall, which was more permanent-looking than what we had in Puyallup. And so, we said, "Well, I guess this is where we're going to stay for awhile." [7] Over 13,000 inmates were incarcerated at Minidoka, most originally from urban areas like Seattle and Portland. Many inmates tried to make the best of their situation. The only positive aspect of life at Minidoka, Aki remembered, was “the togetherness and the community spirit”. There was limited self-governance through an elected camp council, and inmate-led religious services, recreation activities, and a co-op. [8] “We had community singing. And just, then later on they did community dances in the mess hall, you know. And so, that we felt the bonding and the togetherness. And I thought that was good and people were helping each other, and friendly.” [9] Eventually schools were set up in the detention center, and Aki was able to get her high school diploma while incarcerated, though she said it was uneventful. [10] A lifelong friendship

One of the people that was important to Aki Kurose’s life was Floyd Schmoe, a naturalist and Quaker activist who protested the incarceration of Japanese Americans both during and after the war.

Aki recalled of Floyd, “He was a professor at the University of Washington, a forestry professor. And he housed many Japanese students that came from Yakima, Wapato, whatever. The family always took in students. And I started attending Friends Center -- Friends meeting, which is church. And he just kind of adopted me, and said, "Hey, you're going to be our daughter." And so I'd go in and out of his house all the time. And his wife was very, very nice, and I got to know the whole family.” Aki even lived with the family of Ruth, Floyd’s wife, in Kansas when she went to Friends University for her freshman year of college. [13]

They worked together and remained lifelong friends. “He is just the most uncanny person I've ever known,” Aki once said. “He's very bright, very giving; he's just a very nice person. And I think I feel real honored to be his friend.” Floyd was even with Aki the night she died. At that moment he recalled “All I remember saying, over and over again, "We love you, we love you." [14] Life after the war

After graduating college in 1948, Aki got married and got involved in peace activism through her work with the AFSC. “I realized what war can do and the injustices that occur [because of] war. There is no justice when war takes place. And my folks emphasized the fact that [our] incarceration was due to war, this was an injustice due to war. And that we should always make sure that there is no more war, and we should work for peace.” [15]

Through AFSC, Kurose also got involved in the local open housing movement in the 1950s, which fought to remove discriminatory housing practices that resulted in segregation. In the 1960s, Kurose joined efforts led by the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) to desegregate schools, housing, and unions. During this time she and other parents in the neighborhood worked together to start a preschool which became the first Head Start program in Washington State. It was this experience that led Kurose to decide to become a teacher. [16] When Kurose began teaching in 1974, Seattle was beginning an effort to desegregate its schools through busing, but also staffing mandates. She recalls, “they were desegregating the schools and it came to the attention of the school board that the staff was not desegregated.” And so the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) released a mandate that “no minority teacher could teach in a minority impacted school,” and Kurose was transferred from the predominantly Black MLK Elementary School to the mostly white, affluent Laurelhurst Elementary, replacing a beloved teacher in the process. [17] The parent community was very resistant to the transfer. She said, “There was one parent that came and said, "You know, the only reason you have this job is because you're a minority, I don't think you're a good teacher at all, the only reason you have this job is you're a minority, and you've displaced and replaced one of the best teachers in the district." [17] Although she was heavily criticized as a minority teacher at predominantly white school, she eventually became one of the most loved and respected teachers. “Some of my greatest critics became my strongest advocates,” she said. She was awarded Seattle Teacher of the Year in 1985, and after her death a Seattle middle school was named in her honor. [18] What Aki Kurose means to me

This was how I learned about Aki Kurose, as a 7th grader at that exact school, where there is a glass display case containing an exhibit about her life’s work. Reading about her legacy, I admired what she was able to do with her life. Her experience in the incarceration camps led her to to fight for peace and against discrimination afterwards. Learning about her also changed my perspective on history, teaching me to make sure I got all narratives of a story, so that I can form my own opinion.

Although throughout my life, I have felt lucky not to experience being stereotyped a lot, reading articles about the slander and violence against Asian Americans during the pandemic made me sad. Thoughts crept into the back of my head like feeling that this kind of behavior is considered acceptable by society. Or that even if they don’t say anything to your face or do anything, people may be judging you if you cough close to them. You are aware that people may be judging you just by your appearance or background. And like Aki, I feel empathy for others. If you take homelessness for example, there are people that are suffering without a home and who are not treated with the same respect as others. They are given weird looks, and others assume things about them. Through her work she was able to help fix injustices. Her story inspired me to advocate for change.

This piece relied heavily on oral histories conducted with Aki Kurose and Floyd Schmoe for Densho. Many thanks to all involved in sharing and preserving these stories for future generations. To read, watch, or listen to more interviews and stories of the Japanese American incarceration experience from those who lived it, visit the Densho Digital Repository at https://ddr.densho.org/

Footnotes:

Bibliography

Transcript, Akiko Kurose Interview I, 17 July 1997, (Full). Densho Digital Archive. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-41-1/

Transcript, Floyd Schmoe Interview I, 10 June 1998, (Full). Densho Digital Archive. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-83-1/ Executive Order: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5730250 Matsumoto, Nancy. "Aki Kurose," Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Aki%20Kurose Niiya, Brian. "Executive Order 9066," Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Executive%20Order%209066 Niiya, Brian. "Minidoka," Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Minidoka Ott, Jennifer. “Aki Kurose,” HistoryLink. https://www.historylink.org/File/9339 Tsutakawa, Mayumi. "Floyd Schmoe," Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Floyd%20Schmoe Image citations:

Written by Karen. Introduction When the city of Seattle is mentioned, some of the first things that come to most people's minds are rain, the Space Needle, and of course, coffee. The birthplace of Starbucks and home to a variety of coffee houses, Seattle is full of rich coffee culture and its influence has spread across generations. From year to year, Seattle usually finds its way somewhere in the top 10 or top 5 cities for coffee lovers.[1] A 2020 study found that there are 56 coffee shops per 100,000 residents.[2] The city also has the highest ratio of Starbucks cafes per capita - around one café for every 4000 people.[3] Seattle’s cold, rainy weather makes it the perfect place to sip a warm cup of freshly brewed coffee. There's just something about being subjected to the soggy weather the majority of the year that makes having a warm cup of coffee in your hand a must. The extra jolt of caffeine, the idea of getting cozy at a café, and the seasonal comfort. General Coffee House History Coffee Houses are a staple of modern society. Jonathan Morris, coffee historian, has identified the following key moments in the history of modern coffee houses, beginning in the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1500s.[4] Liquor and bars were banned to most practicing Muslims - coffee was deemed a legitimate non-intoxicating drink by religious officials, and Ottoman coffee houses provided a democratic space for Muslim men to gather and socialize outside the mosque. Coffee culture developed rapidly, and coffee houses quickly became known as meeting places for political discussion. Coffee’s affordability and accessibility eroded centuries of social norms of social class. By the early 1500s, coffee shops were outlawed by Ottoman officials, as they believed that the gathering places encouraged disruption of ruling in the country. Coffee then spread throughout Europe in the mid-1600s, primarily through metropolitan cities like Vienna, London, and Paris. In Europe, the process of adding milk, cream, and sugar was introduced. Just like in the Middle East, European coffeehouses were used to enable patrons to stage debates, read the local paper, and converse. From the 1850s to the 1950s, coffee was transformed into an industrial product in the United States. Coffee houses spread to the Americas early on in their colonization. After the Second World War, coffee became a global commodity. Seattle Coffee History Where did Seattle get its affiliation with coffee from? Seattle has a long history of coffee, beginning with roasteries selling out of Pike Place Market. The first began in 1895 when Oscar Delaloyes opened Seattle Tea and Coffee in the Pike Place Market after finding some coffee beans on the ground and roasting them.[5] The popular roastery Manning’s, followed suit in 1908. During the late 60s’ and early 70s, coffee houses boomed across the United States, and Seattleites welcomed coffee house culture. In particular, the city gained a reputation for European-style espresso shots, aided in large part by the city’s first coffee cart, Monorail Espresso, introduced in 1980.[6] The founding of a new coffee store by Jerry Baldwin, Gordon Bowker, and Zev Siegel in 1971 in the cobblestone streets of Pike Place Market brought a new name to the Seattle coffee scene—Starbucks.6 The original Starbucks focused on beans rather than brewed drinks. That changed when Starbucks was bought by Howard Schultz in 1987, who noticed the popularity of Italian-inspired coffee, and shifted the focus of the company to providing prepared drinks.[6] Without a doubt, Starbucks altered American coffee culture significantly as the hallmark of the “second wave” of coffee culture. With the rise of popular chains like Starbucks and Peet’s coffee, coffee became a part of daily life, and specialty drinks like the Frappuccino focused on the creativity of the drink. Starbucks's widespread growth also led to the company buying up the competition (like Seattle’s Best Coffee) and putting local coffee shops out of business. The coffee giant scoops the best locations and forces independent shops to do business in less-trafficked areas.[7] In many cities, the appearance of a Starbucks is a sign that a neighborhood is about to be gentrified.[8] Independent Coffee Shops Almost immediately, in response to the homogeneity of second wave coffee houses, a “third wave” of coffee culture began to emerge in Seattle as coffee aficionados began pulling away from major coffee chains and began seeking out smaller local shops. These local shops were able to compete with Starbucks by offering what they didn’t: artisanal quality coffee. Now it is common to go into an independent coffee shop and be provided with information about your coffee’s farm, harvest date, processing style, roast date, coffee variety, and tasting notes. [9] However, what makes each corner café unique depends on the shop. There are coffee shops on nearly every block, and espresso is available at hundreds of walk-up and drive-through coffee shops. With all the competition, coffee houses must find a way to differentiate themselves from the rest of the pack. Whether that means offering ice cream, fast Wi-Fi, folk music, café cats, or bikini baristas, each independent coffee business provides a completely unique experience. Coffee houses offer unique environments that have been cultivated around the city for people to gather, work, and feel at home. Swipe through for espresso-sized servings of Seattle's coffee history as seen through photos in the MOHAI collection. Footnotes

Additional sources: Borg, Shannon. "Seattle Coffee Guide: Locally Roasted Beans" (Coffee: How Seattle Built a Culture). Seattle Magazine. Retrieved 15 November 2011. https://seattlemag.com/locally-roasted-beans Dickerman, Sarah. “Seattle Coffee Guide: The Evolution of Coffee.” Seattle Magazine, November 27, 2018. https://seattlemag.com/article/seattle-coffee-guide-evolution-coffee. Grambush, Jacklyn. “A Brief History of Coffee in Seattle.” The Culture Trip, October 23, 2017. https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/usa/washington/articles/a-brief-history-of-coffee-in-seattle/. “History of Coffee in Seattle.” Bartell Drugs, August 25,2021. https://www.bartelldrugs.com/blog/history-of-coffee-in-seattle/. Michelman, Jordan. “How the Pacific Northwest Became a Coffee Paradise.” Eater Portland, June 14, 2021. https://pdx.eater.com/22436234/history-coffee-pacific-northwest-portland-seattle. Tomky, Naomi. “Where to Find the Classic Coffee Shops That Made Seattle World Famous.” Thrillist, March 18, 2019. https://www.thrillist.com/drink/seattle/classic-seattle-coffee-shops-starbucks-history. Stork, Christina. “The History of Peet's Coffee.” Peet's Coffee, July 16, 2021. https://www.peets.com/blogs/peets/the-history-of-peets-coffee. Yeah, Joon Han-Mann. “Seattle Coffee Scene Becomes Young Again.” Edited by Jaewook Jung. Lotte Hotels & Resorts Magazine, July 2020. https://www.lottehotelmagazine.com/en/food_style_detail?no=328.

Written and created by Gabriella and Sue

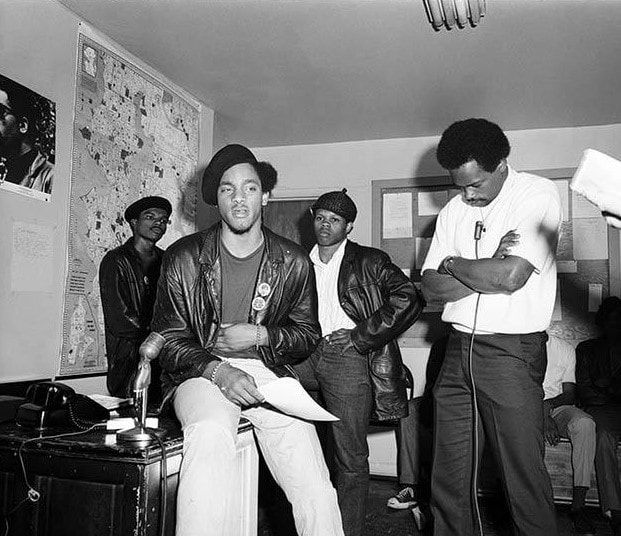

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in 1966 in Oakland, CA by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. In the spring of 1968 the Seattle chapter, the first outside of California, was co-founded by Aaron Dixon and his brother Elmer. Like other branches, the Seattle chapter opened health clinics, ran a free breakfast program for children, and protected citizens from police harassment. While active, the Black Panthers were targeted by the FBI (1). This included tactics such as killing party leaders, smear campaigns, and arresting members on trumped up charges. Though the Seattle chapter only lasted 10 years, it created lots of change. Here in Seattle we have one of the last medical clinics started by the Panthers. Across the nation, schools provide free and reduced price breakfast to students, a practice first initiated by the Panthers (2). Though the Panthers no longer operate in an official capacity, their legacy and goals live on.

Explore this interactive map of places and spaces in Seattle tied to the history of the Black Panther Party.

Footnotes

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed