|

10/16/2023 0 Comments Interactive: Women of Seattle ArtsEditor’s note: This piece was created during the 2023 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing. For her project, Nora created a web interactive that spotlighted four different women artists/organizations from a variety of artistic disciplines and time periods. This year's History Lab was inspired by the Museum of History and Industry exhibit Celebrating Pacific Northwest Artists: 25 Years of the Neddy Awards. As a participant, I was prompted to incorporate Seattle art and artists into my research project. As someone who has lived just outside the city her whole life, I wanted to focus on the diverse types of art that have been produced by local artists. As I began research, I started to look up parts of Seattle’s art scene and lesser known stories of artists. The first one I found was Tina Bell. Bell’s story fascinated me as I found it so bizarre that someone who seems so influential could be so relatively obscure. That led me to focus on other women who have helped to shape Seattle’s art scene. Before this project I was oblivious to each of the women I chose to write about. I found it curious that I hadn’t heard of any of them when they all have a huge legacy in Seattle and the Pacific Northwest. Throughout this project I noticed similarities between all these women and how they’ve each been challenged with being underrepresented in their fields. I created this project in order to highlight and showcase their unique stories and accomplishments that so more people can learn about them. I hope that this helps to bring to light their talents and contributions to the arts.

- Nora

0 Comments

This series of Rainy Day History bonus episodes were designed to provide a soundtrack to your MOHAI experience and are best listened to as part of the playlist below. If you’re at the museum, we encourage you to pop in some headphones and listen to the introductions and curated songs while you walk through MOHAI’s core exhibit, True Northwest: The Seattle Journey.

In this playlist, MOHAI Youth Advisors Chelsea and Charlee will introduce three musical pairings hand-picked to complement your exploration of a specific section of True Northwest, then you will get a chance to listen to the songs. Join us on a musical journey through Seattle history! Show Notes:

Episode Transcripts:

Sources:

Explore more:

11/4/2022 1 Comment Aki Kurose: A Life Remembered

By: Nathan D.

Editor’s note: This piece was created during the 2022 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing. Growing up in the Central District

After Pearl Harbor

At that time, Kurose was in her senior year at Garfield High School, and the next day she remembers a teacher saying to her, “Your people bombed Pearl Harbor.” As those words hit her, she suddenly became very aware of her “Japaneseness,” “not in a real positive way, but kind of a scary way,” she remembered. She no longer felt like an equal American anymore. [2]

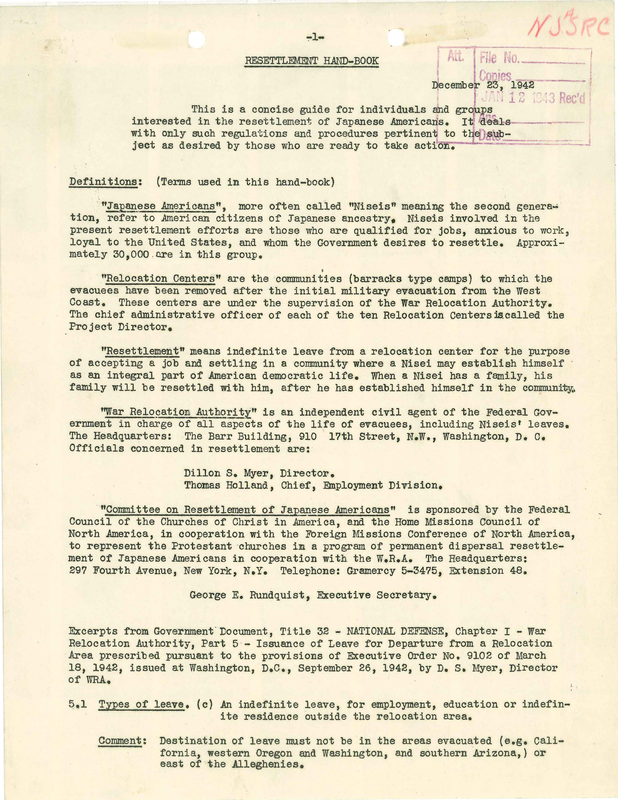

Months later, on February 19th. 1942. President Roosevelt wrote Executive Order 9066 which authorized the exclusion of “any and all persons” from living in established “military zones”. [3]This resulted in the forced removal of Japanese immigrants and Japanese American cities from their homes along the West Coast to incarceration centers monitored by the military. [4]

Aki’s entire family was first moved to the Puyallup Assembly Center (located on the Puyallup Fairgrounds, and called “Camp Harmony” by army officials), along with other Japanese Americans ranging from Western Washington to Alaska. The barracks and shower stalls at the detention facility were mostly communal. Aki, who was raised to be very modest and private, recalled this being “devastating”. [5] The temporary structures were poorly constructed; some were converted animal stalls, and they had no insulation. Aki also remembered, “they gave us army cots and then they gave us these bags and we were to stuff them [with hay] for mattresses…But my sister, Suma, was very asthmatic, so that was terrible. She could not survive with the straw mattresses, you know. And so she spent a lot of time in the hospital in camp, because of her asthma. And [the] medical care was not that adequate either.” [6] After a few months at Puyallup, her family was transferred to the “Minidoka Relocation Center,” in Idaho. The detention center wasn’t finished when incarcerees first arrived, but at least it seemed more stable than the barracks in Puyallup, Aki remembered. “This time they gave us army mattresses, so we didn't have to stuff mattresses when we went there. And there were still the steel army cots and we had to arrange the six beds so that there'd be space enough for us to move around. And then there was the mess hall, which was more permanent-looking than what we had in Puyallup. And so, we said, "Well, I guess this is where we're going to stay for awhile." [7] Over 13,000 inmates were incarcerated at Minidoka, most originally from urban areas like Seattle and Portland. Many inmates tried to make the best of their situation. The only positive aspect of life at Minidoka, Aki remembered, was “the togetherness and the community spirit”. There was limited self-governance through an elected camp council, and inmate-led religious services, recreation activities, and a co-op. [8] “We had community singing. And just, then later on they did community dances in the mess hall, you know. And so, that we felt the bonding and the togetherness. And I thought that was good and people were helping each other, and friendly.” [9] Eventually schools were set up in the detention center, and Aki was able to get her high school diploma while incarcerated, though she said it was uneventful. [10] A lifelong friendship

One of the people that was important to Aki Kurose’s life was Floyd Schmoe, a naturalist and Quaker activist who protested the incarceration of Japanese Americans both during and after the war.

Aki recalled of Floyd, “He was a professor at the University of Washington, a forestry professor. And he housed many Japanese students that came from Yakima, Wapato, whatever. The family always took in students. And I started attending Friends Center -- Friends meeting, which is church. And he just kind of adopted me, and said, "Hey, you're going to be our daughter." And so I'd go in and out of his house all the time. And his wife was very, very nice, and I got to know the whole family.” Aki even lived with the family of Ruth, Floyd’s wife, in Kansas when she went to Friends University for her freshman year of college. [13]

They worked together and remained lifelong friends. “He is just the most uncanny person I've ever known,” Aki once said. “He's very bright, very giving; he's just a very nice person. And I think I feel real honored to be his friend.” Floyd was even with Aki the night she died. At that moment he recalled “All I remember saying, over and over again, "We love you, we love you." [14] Life after the war

After graduating college in 1948, Aki got married and got involved in peace activism through her work with the AFSC. “I realized what war can do and the injustices that occur [because of] war. There is no justice when war takes place. And my folks emphasized the fact that [our] incarceration was due to war, this was an injustice due to war. And that we should always make sure that there is no more war, and we should work for peace.” [15]

Through AFSC, Kurose also got involved in the local open housing movement in the 1950s, which fought to remove discriminatory housing practices that resulted in segregation. In the 1960s, Kurose joined efforts led by the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) to desegregate schools, housing, and unions. During this time she and other parents in the neighborhood worked together to start a preschool which became the first Head Start program in Washington State. It was this experience that led Kurose to decide to become a teacher. [16] When Kurose began teaching in 1974, Seattle was beginning an effort to desegregate its schools through busing, but also staffing mandates. She recalls, “they were desegregating the schools and it came to the attention of the school board that the staff was not desegregated.” And so the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) released a mandate that “no minority teacher could teach in a minority impacted school,” and Kurose was transferred from the predominantly Black MLK Elementary School to the mostly white, affluent Laurelhurst Elementary, replacing a beloved teacher in the process. [17] The parent community was very resistant to the transfer. She said, “There was one parent that came and said, "You know, the only reason you have this job is because you're a minority, I don't think you're a good teacher at all, the only reason you have this job is you're a minority, and you've displaced and replaced one of the best teachers in the district." [17] Although she was heavily criticized as a minority teacher at predominantly white school, she eventually became one of the most loved and respected teachers. “Some of my greatest critics became my strongest advocates,” she said. She was awarded Seattle Teacher of the Year in 1985, and after her death a Seattle middle school was named in her honor. [18] What Aki Kurose means to me

This was how I learned about Aki Kurose, as a 7th grader at that exact school, where there is a glass display case containing an exhibit about her life’s work. Reading about her legacy, I admired what she was able to do with her life. Her experience in the incarceration camps led her to to fight for peace and against discrimination afterwards. Learning about her also changed my perspective on history, teaching me to make sure I got all narratives of a story, so that I can form my own opinion.

Although throughout my life, I have felt lucky not to experience being stereotyped a lot, reading articles about the slander and violence against Asian Americans during the pandemic made me sad. Thoughts crept into the back of my head like feeling that this kind of behavior is considered acceptable by society. Or that even if they don’t say anything to your face or do anything, people may be judging you if you cough close to them. You are aware that people may be judging you just by your appearance or background. And like Aki, I feel empathy for others. If you take homelessness for example, there are people that are suffering without a home and who are not treated with the same respect as others. They are given weird looks, and others assume things about them. Through her work she was able to help fix injustices. Her story inspired me to advocate for change.

This piece relied heavily on oral histories conducted with Aki Kurose and Floyd Schmoe for Densho. Many thanks to all involved in sharing and preserving these stories for future generations. To read, watch, or listen to more interviews and stories of the Japanese American incarceration experience from those who lived it, visit the Densho Digital Repository at https://ddr.densho.org/

Footnotes:

Bibliography

Transcript, Akiko Kurose Interview I, 17 July 1997, (Full). Densho Digital Archive. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-41-1/

Transcript, Floyd Schmoe Interview I, 10 June 1998, (Full). Densho Digital Archive. https://ddr.densho.org/interviews/ddr-densho-1000-83-1/ Executive Order: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5730250 Matsumoto, Nancy. "Aki Kurose," Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Aki%20Kurose Niiya, Brian. "Executive Order 9066," Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Executive%20Order%209066 Niiya, Brian. "Minidoka," Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Minidoka Ott, Jennifer. “Aki Kurose,” HistoryLink. https://www.historylink.org/File/9339 Tsutakawa, Mayumi. "Floyd Schmoe," Densho Encyclopedia https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Floyd%20Schmoe Image citations:

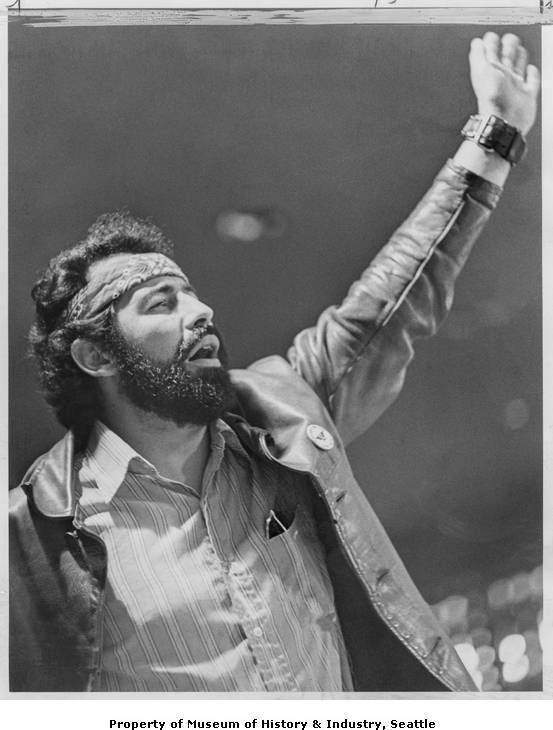

5/9/2021 0 Comments ProfilesFuture content to be added - let us know who you're interested in learning more about! In the meantime, learn more about this great photo in the MOHAI collection of Roberto Maestas at a city council hearing in 1972.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed