|

7/30/2021 0 Comments History of Redlining in SeattleWritten by Cherlyn

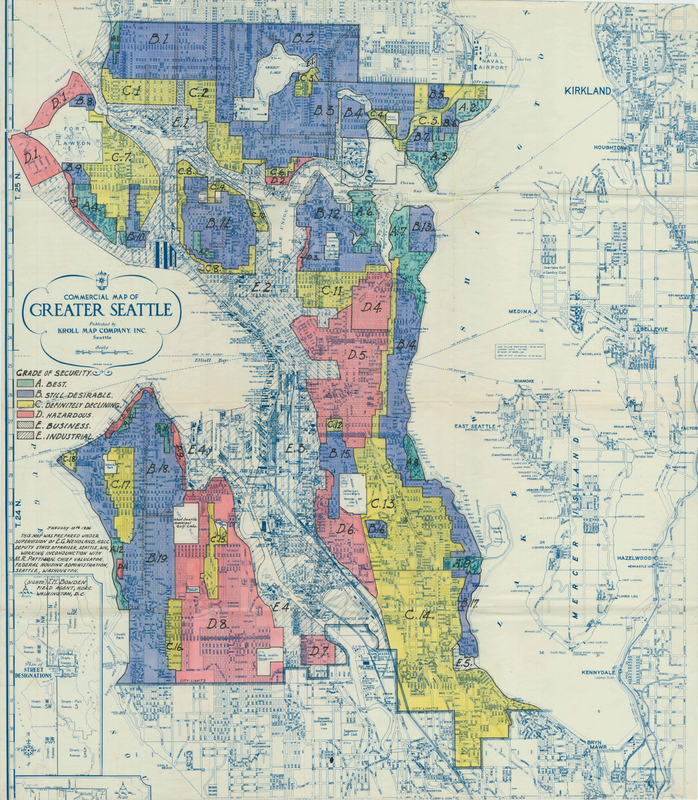

Attempting to stabilize after foreclosures during the Great Depression, the federal government put together maps for banks such as this one from 1936. It shows which neighborhoods are “desirable” based on the predicted safety of mortgages. The desirability of these areas was determined by housing conditions, neighborhood incomes, but also their racial makeup. Armed with this map, banks and financiers began distributing loans with the condition that the proposed land not be inhabited by non-white people to secure home owners that they believed would get them their money's worth. Any neighborhood that allowed non-white residents would automatically be considered “hazardous” (in the red zone, which is where the term redlining comes from). Mortgages for homes in this area were very hard to get, which prevented communities of color from accumulating wealth through property ownership. The “best” neighborhoods were quickly bought out by white customers and Seattle’s communities of color were further pushed into “hazardous” ones. Home owners, neighborhood groups, real estate agents, and developers in white-dominated communities also enforced residential segregation by putting racially restrictive housing covenants into property deeds that stated that homes couldn’t be sold to specific ethnic or racial groups. By the 1970’s, the Central District was home to about 70 percent of the city’s Black population. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down racist housing covenants in 1948, though some Seattle deeds still contain them. In 1968, local and federal fair housing laws were put into place that made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of race when selling or renting housing. These efforts were led by community leaders alongside the civil rights movement. In Seattle, non-discriminatory housing was passed by the City Council and signed by the mayor, only three weeks after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Even with this implementation of “equality”, unwritten or altered versions of redlining policies and overt discrimination continued to be used into the next decade. We still see the impacts of these policies in the racial makeup of neighborhoods and schools today. According to a study of 2018 Census Bureau data done for the Seattle Times, North Seattle neighborhoods remain mostly white; Madison Park/Broadmoor for example, was tied for least-diverse with Fauntelroy/Gatewood in West Seattle, with a population of 89% white people. Southern neighborhoods like Federal Way, White Center, and Rainier Beach were ranked among the most diverse; in the northern end of Federal Way, no single racial group made up more than 28% of the population. With less access to generational wealth due to these historic practices and continuing income inequality, communities of color continue to be subjected to lower quality living conditions because of an inability to acquire desirable property. Resilient communities have formed in these formerly “dangerous” areas, but forces like gentrification threaten the stability and resources they have built for themselves. Sources:

0 Comments

Written by Vance

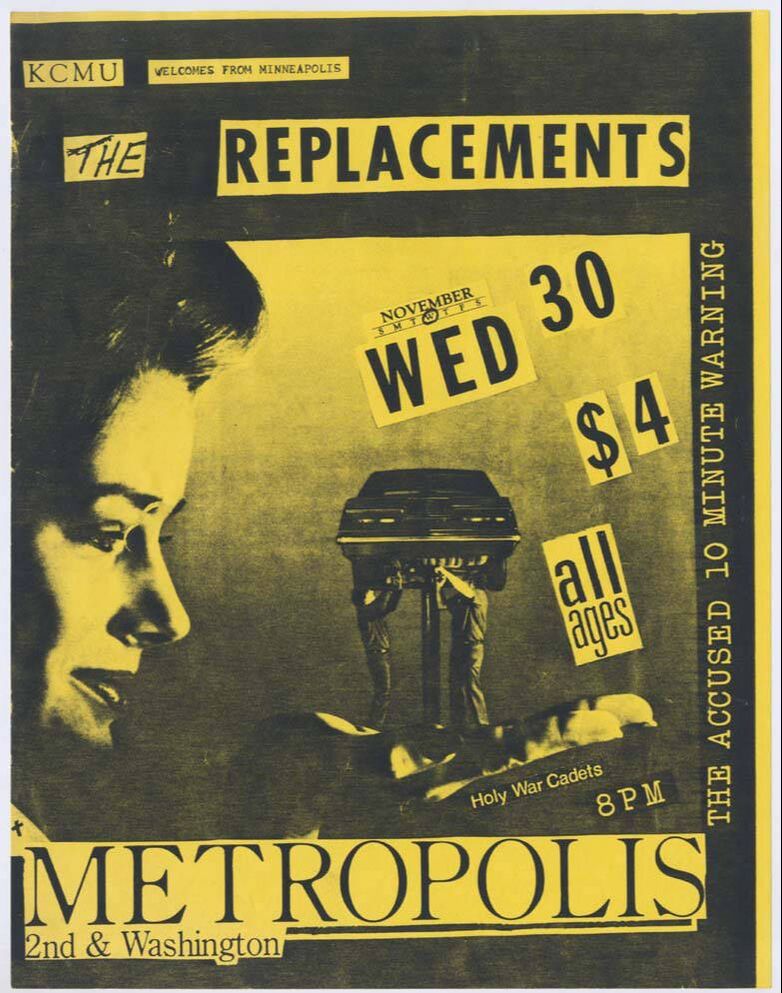

The Crocodile (formerly the Crocodile Café) Established right before the Grunge explosion in 1991, up until the pandemic this café and rock bar continued to be a hotspot for up-and-coming artists of all genres. Despite a brief closure, the club managed to stay in its original Belltown location for nearly 30 years. The legendary venue hosted such artists as Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Cheap Trick, R.E.M., Mudhoney, Yoko Ono, and many more. The club was even named #7 on Rolling Stone Magazine’s Best Clubs in America in 2013. The owners announced during the pandemic that they would be closing the original location and re-opening a few blocks away. The Showbox This is one of the oldest clubs on the list, established in 1939. It originally hosted big-name jazz shows from the likes of Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, and Dizzy Gillespie. The more local jazz scene was located along Jackson Street. The iconic art-deco theater also supported the rise of grunge, with bands like Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, and Nirvana playing multiple shows. That support has paid off, as members of those bands lent their voice to a petition to make the Showbox an official City of Seattle Landmark, saving it from demolition. You can still visit the club today, tucked right in between Pike Place Market and the Seattle Art Museum. El Corazón This club has gone by many names, including Graceland, Sub-Zero, The Eastlake East Café, Au Go Go, as well as the aptly named Off Ramp Café, and remained in its original 1910 building until very recently. A combination of rising property taxes and noise complaints led to the forced closure and demolition of the historic building, and it is being replaced with two apartment buildings. However, the owner has plans to move the club to a location close by the original. The club was the site of the first Pearl Jam show, then called Mookie Blaylock, and was known for hosting many grunge-era bands in their early days. Re-Bar Opened in 1990, this iconic LGBTQ bar has hosted all sorts of shows from Grunge bands to stand-up comedy to drag performances. It was also home to the infamous “Nevermind Triskaidekaphobia,” Nirvana’s release party for the titular album, where the band members were kicked out after starting a food fight. The club held out against development in the neighborhood for years, but sadly the club didn’t survive the Covid-19 pandemic and has closed its doors until further notice. The owners posted the announcement on their Facebook page in May 2020, linking the Beatles’ “Hello, Goodbye” in a hopeful farewell, with plans to relocate to south Seattle in Fall 2021. The Central Saloon By far the oldest on the list, this tavern/venue opened in 1892 after the Seattle Fire. Through many changes in name and ownership, this historic location continues to host musicians of all genres. However, one downside to remaining in the same 1800s building in Pioneer square is that the acoustics of the venue have not improved. Even after almost 100 years, the club remained an essential part of the Seattle grunge explosion. It was reportedly the location where Sub-Pop Records owners saw Nirvana play for the first time, leading to their first album recorded under the Sub-Pop label. Their website claims the title of the “birthplace of grunge,” as many now world-famous bands made their start playing The Central. Moe’s Mo’Roc’n Café This café opened at the peak of the Grunge era in 1993 and only lasted four years, until its closure in 1997. According to The Stranger, this club was just as influential as The Crocodile despite its short lifespan. Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture has even made the original circus-inspired entrance arch a permanent addition to their collection. However, 5 years after the closure the original owners were able to resurrect the club as Neumo’s (pronounced New Moe’s) in early 2003. The new club featured an updated sound system and expanded standing room, and still hosts primarily local and indie-rock acts today. RKCNDY Pronounced “Rock Candy,” this iconic club was an all-ages rock haven during the era of the Teen Dance Ordinance, and was featured in our Rainy Day History Podcast for that very reason (Episode 12 - I need the volume higher). The club was prolific, featuring performances from every Seattle band of the 90s, including traveling acts from Radiohead, Joan Jett, Marilyn Manson, and The Verve. Opening in 1991 and closing on Halloween night 1999, this club’s life spanned the length of the Grunge era, inspiring the youth of Seattle to carry the music tradition into the next century. Formerly located south of the Re-Bar by the offramp, there now sits a SpringHill Suites Marriott hotel.

Sources:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed