|

Each year the MOHAI Youth Advisors work together on a culminating group project that they envision, plan, and create together. Last year, the 2022-23 MYA cohort designed and produced a coloring book that serves as a love letter to the history, places, people, and cultures of Seattle. Together they brainstormed and selected topics, drew and designed images, researched and wrote snapshot histories, and designed the look and feel of the book. We have a limited number of risograph copies beautifully printed and assembled by Paper Press Punch that will be distributed at MOHAI programs and to community partners for free! You can also print your own copy from the pdf below, formatted for 8.5 x 11” paper. Access the MOHAI Online Collection to view the historic photos that inspired the pages of this coloring book (and more!) via mohai.org/collections Share your colored pages with us on Instagram @mohaiteens!

0 Comments

By Justin L. Editor’s note: This piece was created during the 2023 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing.

In classic ask-for-forgiveness-not-permission mentality, this “Good Will Committee” of “leading Seattle citizens” took the towering pole to bring back to their city. [4] While one might expect physical violence or deceitful manipulation from such an event, none was reported by the expedition party. Just the audacity of showing up on strangers’ shores and treating their home like a souvenir shop. According to an account by third mate R. D. McGillvery, “the Indians were all away fishing, except for one who stayed in his house and looked scared to death. We picked out the best looking totem pole... we chopped it down - just like you'd chop down a tree. It was too big to roll down the beach, so we sawed it in two.” [3] In a lawsuit filed months later by the original owners of the totem pole, James Clise who was the ringleader and Acting President of the Commerce responded that “there were two decrepit Indians which we finally succeeded in interviewing, who made no objection to our taking the pole to Seattle.” [3]

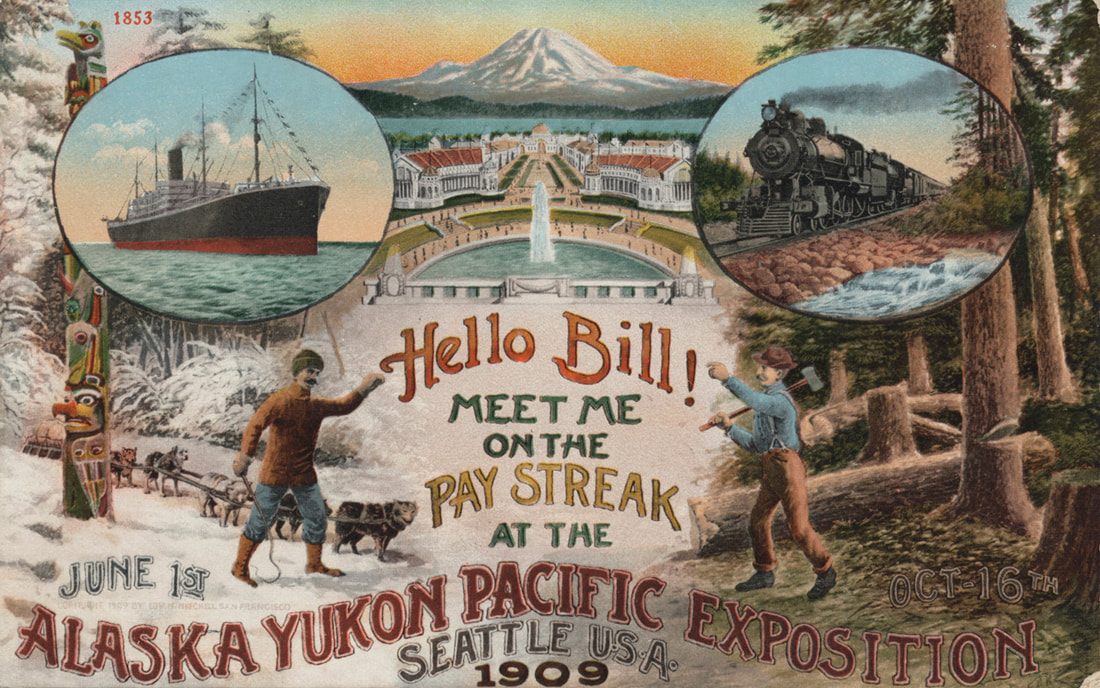

Attorney William H. Thompson, speaking on behalf of his eight defendants, justified the act saying that “here [in Seattle] the totem will voice the natives' deeds with surer speech than if lying prone on moss and fern on the shore of Tongass Island.” [3] To state this presumes that not only does Native culture belong to all Americans, but also that the preservation of Native culture requires the magnanimous aid of white people, who will truly appreciate and help elevate its worth. Both are untrue, but these beliefs were on full display at the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition (AYPE) of 1909, where the totem pole served as a poster child for the first world’s fair hosted in Seattle, the ‘City of Totems’.

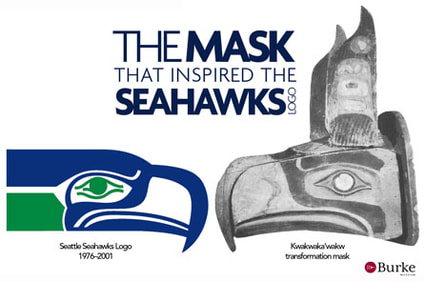

The fair positioned Seattle as a shining city on the edge of a vast American empire. In the face of unprecedented growth of the Seattle economy, those who were wistful for the pastoral past became fascinated with the wilderness, and romanticized it. This was an untapped market, Seattle noticed. Positioning Native people and culture at the fair as backwards, exotic, and mysterious helped communicate to fairgoers that Native land was their visit and take from, and Seattle was their Gateway to the North. It offered the adventure of a lifetime, and was the frontier to a spectacle. The ways Native people were on display at the fair, however, was not simply harmless fascination. It chipped away at Native sovereignty, and actually reflects hatred. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz and Dina Gilio-Whitaker, co-authors of “All The Real Indians Died Off” and 20 Other Myths About Native Americans, bust the myth that all “Native American Culture Belongs to all Americans.” They note that scholar Rayna Green is one of the first to use the concept “Playing Indian”, to unpack the ways in which Americans’ obsession with the “vanishing race'' at times “translated into trying to become them, or at least using them to project new images of themselves as they settled into North America.” [8] Seattlelites did not love Native culture. They pitied upon Native culture because compared with their industrialized standards of living, they saw Native people as noble savages stuck in the past. And by co-opting their culture and ‘ownership’ of the wilderness, they sought to replace them.

Footnotes:

A webzine by Jasmine Z. Editor’s note: This piece was created during the 2022 session of History Lab, a summer intensive for high school students interested in local history and storytelling. Over the course of two weeks, participants explore creative ways to interpret and share history, conduct research, and produce a work of historical interpretation in a digital medium on a topic of their choosing. Written by Karen. Introduction When the city of Seattle is mentioned, some of the first things that come to most people's minds are rain, the Space Needle, and of course, coffee. The birthplace of Starbucks and home to a variety of coffee houses, Seattle is full of rich coffee culture and its influence has spread across generations. From year to year, Seattle usually finds its way somewhere in the top 10 or top 5 cities for coffee lovers.[1] A 2020 study found that there are 56 coffee shops per 100,000 residents.[2] The city also has the highest ratio of Starbucks cafes per capita - around one café for every 4000 people.[3] Seattle’s cold, rainy weather makes it the perfect place to sip a warm cup of freshly brewed coffee. There's just something about being subjected to the soggy weather the majority of the year that makes having a warm cup of coffee in your hand a must. The extra jolt of caffeine, the idea of getting cozy at a café, and the seasonal comfort. General Coffee House History Coffee Houses are a staple of modern society. Jonathan Morris, coffee historian, has identified the following key moments in the history of modern coffee houses, beginning in the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1500s.[4] Liquor and bars were banned to most practicing Muslims - coffee was deemed a legitimate non-intoxicating drink by religious officials, and Ottoman coffee houses provided a democratic space for Muslim men to gather and socialize outside the mosque. Coffee culture developed rapidly, and coffee houses quickly became known as meeting places for political discussion. Coffee’s affordability and accessibility eroded centuries of social norms of social class. By the early 1500s, coffee shops were outlawed by Ottoman officials, as they believed that the gathering places encouraged disruption of ruling in the country. Coffee then spread throughout Europe in the mid-1600s, primarily through metropolitan cities like Vienna, London, and Paris. In Europe, the process of adding milk, cream, and sugar was introduced. Just like in the Middle East, European coffeehouses were used to enable patrons to stage debates, read the local paper, and converse. From the 1850s to the 1950s, coffee was transformed into an industrial product in the United States. Coffee houses spread to the Americas early on in their colonization. After the Second World War, coffee became a global commodity. Seattle Coffee History Where did Seattle get its affiliation with coffee from? Seattle has a long history of coffee, beginning with roasteries selling out of Pike Place Market. The first began in 1895 when Oscar Delaloyes opened Seattle Tea and Coffee in the Pike Place Market after finding some coffee beans on the ground and roasting them.[5] The popular roastery Manning’s, followed suit in 1908. During the late 60s’ and early 70s, coffee houses boomed across the United States, and Seattleites welcomed coffee house culture. In particular, the city gained a reputation for European-style espresso shots, aided in large part by the city’s first coffee cart, Monorail Espresso, introduced in 1980.[6] The founding of a new coffee store by Jerry Baldwin, Gordon Bowker, and Zev Siegel in 1971 in the cobblestone streets of Pike Place Market brought a new name to the Seattle coffee scene—Starbucks.6 The original Starbucks focused on beans rather than brewed drinks. That changed when Starbucks was bought by Howard Schultz in 1987, who noticed the popularity of Italian-inspired coffee, and shifted the focus of the company to providing prepared drinks.[6] Without a doubt, Starbucks altered American coffee culture significantly as the hallmark of the “second wave” of coffee culture. With the rise of popular chains like Starbucks and Peet’s coffee, coffee became a part of daily life, and specialty drinks like the Frappuccino focused on the creativity of the drink. Starbucks's widespread growth also led to the company buying up the competition (like Seattle’s Best Coffee) and putting local coffee shops out of business. The coffee giant scoops the best locations and forces independent shops to do business in less-trafficked areas.[7] In many cities, the appearance of a Starbucks is a sign that a neighborhood is about to be gentrified.[8] Independent Coffee Shops Almost immediately, in response to the homogeneity of second wave coffee houses, a “third wave” of coffee culture began to emerge in Seattle as coffee aficionados began pulling away from major coffee chains and began seeking out smaller local shops. These local shops were able to compete with Starbucks by offering what they didn’t: artisanal quality coffee. Now it is common to go into an independent coffee shop and be provided with information about your coffee’s farm, harvest date, processing style, roast date, coffee variety, and tasting notes. [9] However, what makes each corner café unique depends on the shop. There are coffee shops on nearly every block, and espresso is available at hundreds of walk-up and drive-through coffee shops. With all the competition, coffee houses must find a way to differentiate themselves from the rest of the pack. Whether that means offering ice cream, fast Wi-Fi, folk music, café cats, or bikini baristas, each independent coffee business provides a completely unique experience. Coffee houses offer unique environments that have been cultivated around the city for people to gather, work, and feel at home. Swipe through for espresso-sized servings of Seattle's coffee history as seen through photos in the MOHAI collection. Footnotes

Additional sources: Borg, Shannon. "Seattle Coffee Guide: Locally Roasted Beans" (Coffee: How Seattle Built a Culture). Seattle Magazine. Retrieved 15 November 2011. https://seattlemag.com/locally-roasted-beans Dickerman, Sarah. “Seattle Coffee Guide: The Evolution of Coffee.” Seattle Magazine, November 27, 2018. https://seattlemag.com/article/seattle-coffee-guide-evolution-coffee. Grambush, Jacklyn. “A Brief History of Coffee in Seattle.” The Culture Trip, October 23, 2017. https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/usa/washington/articles/a-brief-history-of-coffee-in-seattle/. “History of Coffee in Seattle.” Bartell Drugs, August 25,2021. https://www.bartelldrugs.com/blog/history-of-coffee-in-seattle/. Michelman, Jordan. “How the Pacific Northwest Became a Coffee Paradise.” Eater Portland, June 14, 2021. https://pdx.eater.com/22436234/history-coffee-pacific-northwest-portland-seattle. Tomky, Naomi. “Where to Find the Classic Coffee Shops That Made Seattle World Famous.” Thrillist, March 18, 2019. https://www.thrillist.com/drink/seattle/classic-seattle-coffee-shops-starbucks-history. Stork, Christina. “The History of Peet's Coffee.” Peet's Coffee, July 16, 2021. https://www.peets.com/blogs/peets/the-history-of-peets-coffee. Yeah, Joon Han-Mann. “Seattle Coffee Scene Becomes Young Again.” Edited by Jaewook Jung. Lotte Hotels & Resorts Magazine, July 2020. https://www.lottehotelmagazine.com/en/food_style_detail?no=328.

Written and created by Gabriella and Sue

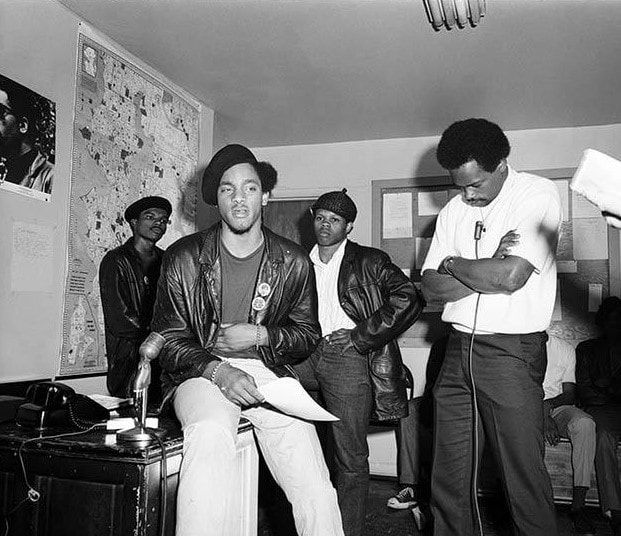

The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was founded in 1966 in Oakland, CA by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. In the spring of 1968 the Seattle chapter, the first outside of California, was co-founded by Aaron Dixon and his brother Elmer. Like other branches, the Seattle chapter opened health clinics, ran a free breakfast program for children, and protected citizens from police harassment. While active, the Black Panthers were targeted by the FBI (1). This included tactics such as killing party leaders, smear campaigns, and arresting members on trumped up charges. Though the Seattle chapter only lasted 10 years, it created lots of change. Here in Seattle we have one of the last medical clinics started by the Panthers. Across the nation, schools provide free and reduced price breakfast to students, a practice first initiated by the Panthers (2). Though the Panthers no longer operate in an official capacity, their legacy and goals live on.

Explore this interactive map of places and spaces in Seattle tied to the history of the Black Panther Party.

Footnotes

7/30/2021 0 Comments History of Redlining in SeattleWritten by Cherlyn

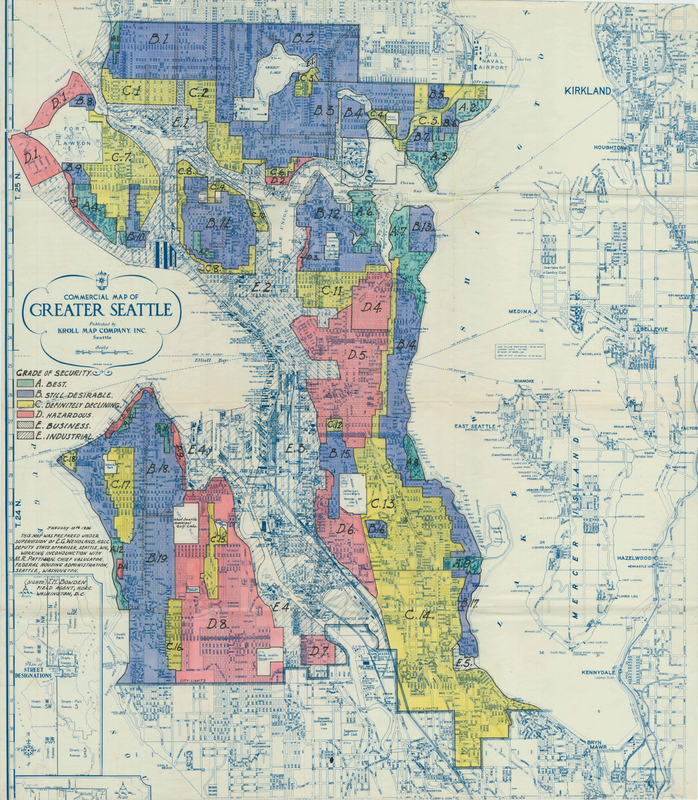

Attempting to stabilize after foreclosures during the Great Depression, the federal government put together maps for banks such as this one from 1936. It shows which neighborhoods are “desirable” based on the predicted safety of mortgages. The desirability of these areas was determined by housing conditions, neighborhood incomes, but also their racial makeup. Armed with this map, banks and financiers began distributing loans with the condition that the proposed land not be inhabited by non-white people to secure home owners that they believed would get them their money's worth. Any neighborhood that allowed non-white residents would automatically be considered “hazardous” (in the red zone, which is where the term redlining comes from). Mortgages for homes in this area were very hard to get, which prevented communities of color from accumulating wealth through property ownership. The “best” neighborhoods were quickly bought out by white customers and Seattle’s communities of color were further pushed into “hazardous” ones. Home owners, neighborhood groups, real estate agents, and developers in white-dominated communities also enforced residential segregation by putting racially restrictive housing covenants into property deeds that stated that homes couldn’t be sold to specific ethnic or racial groups. By the 1970’s, the Central District was home to about 70 percent of the city’s Black population. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down racist housing covenants in 1948, though some Seattle deeds still contain them. In 1968, local and federal fair housing laws were put into place that made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of race when selling or renting housing. These efforts were led by community leaders alongside the civil rights movement. In Seattle, non-discriminatory housing was passed by the City Council and signed by the mayor, only three weeks after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Even with this implementation of “equality”, unwritten or altered versions of redlining policies and overt discrimination continued to be used into the next decade. We still see the impacts of these policies in the racial makeup of neighborhoods and schools today. According to a study of 2018 Census Bureau data done for the Seattle Times, North Seattle neighborhoods remain mostly white; Madison Park/Broadmoor for example, was tied for least-diverse with Fauntelroy/Gatewood in West Seattle, with a population of 89% white people. Southern neighborhoods like Federal Way, White Center, and Rainier Beach were ranked among the most diverse; in the northern end of Federal Way, no single racial group made up more than 28% of the population. With less access to generational wealth due to these historic practices and continuing income inequality, communities of color continue to be subjected to lower quality living conditions because of an inability to acquire desirable property. Resilient communities have formed in these formerly “dangerous” areas, but forces like gentrification threaten the stability and resources they have built for themselves. Sources:

Written by Vance

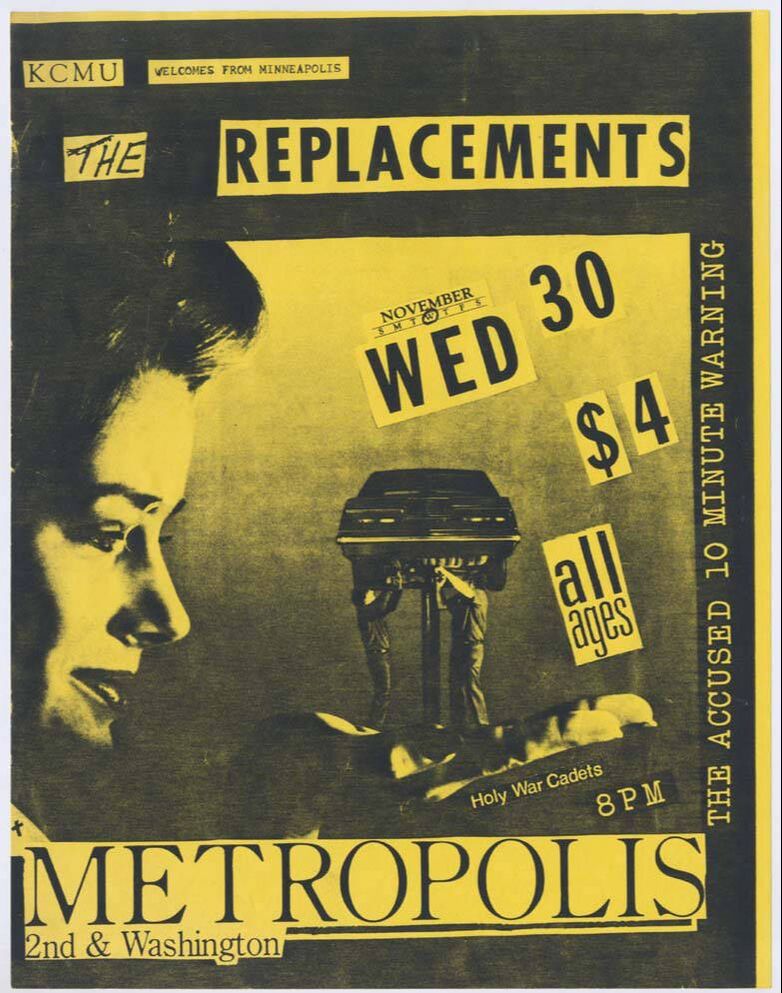

The Crocodile (formerly the Crocodile Café) Established right before the Grunge explosion in 1991, up until the pandemic this café and rock bar continued to be a hotspot for up-and-coming artists of all genres. Despite a brief closure, the club managed to stay in its original Belltown location for nearly 30 years. The legendary venue hosted such artists as Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Cheap Trick, R.E.M., Mudhoney, Yoko Ono, and many more. The club was even named #7 on Rolling Stone Magazine’s Best Clubs in America in 2013. The owners announced during the pandemic that they would be closing the original location and re-opening a few blocks away. The Showbox This is one of the oldest clubs on the list, established in 1939. It originally hosted big-name jazz shows from the likes of Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, and Dizzy Gillespie. The more local jazz scene was located along Jackson Street. The iconic art-deco theater also supported the rise of grunge, with bands like Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, and Nirvana playing multiple shows. That support has paid off, as members of those bands lent their voice to a petition to make the Showbox an official City of Seattle Landmark, saving it from demolition. You can still visit the club today, tucked right in between Pike Place Market and the Seattle Art Museum. El Corazón This club has gone by many names, including Graceland, Sub-Zero, The Eastlake East Café, Au Go Go, as well as the aptly named Off Ramp Café, and remained in its original 1910 building until very recently. A combination of rising property taxes and noise complaints led to the forced closure and demolition of the historic building, and it is being replaced with two apartment buildings. However, the owner has plans to move the club to a location close by the original. The club was the site of the first Pearl Jam show, then called Mookie Blaylock, and was known for hosting many grunge-era bands in their early days. Re-Bar Opened in 1990, this iconic LGBTQ bar has hosted all sorts of shows from Grunge bands to stand-up comedy to drag performances. It was also home to the infamous “Nevermind Triskaidekaphobia,” Nirvana’s release party for the titular album, where the band members were kicked out after starting a food fight. The club held out against development in the neighborhood for years, but sadly the club didn’t survive the Covid-19 pandemic and has closed its doors until further notice. The owners posted the announcement on their Facebook page in May 2020, linking the Beatles’ “Hello, Goodbye” in a hopeful farewell, with plans to relocate to south Seattle in Fall 2021. The Central Saloon By far the oldest on the list, this tavern/venue opened in 1892 after the Seattle Fire. Through many changes in name and ownership, this historic location continues to host musicians of all genres. However, one downside to remaining in the same 1800s building in Pioneer square is that the acoustics of the venue have not improved. Even after almost 100 years, the club remained an essential part of the Seattle grunge explosion. It was reportedly the location where Sub-Pop Records owners saw Nirvana play for the first time, leading to their first album recorded under the Sub-Pop label. Their website claims the title of the “birthplace of grunge,” as many now world-famous bands made their start playing The Central. Moe’s Mo’Roc’n Café This café opened at the peak of the Grunge era in 1993 and only lasted four years, until its closure in 1997. According to The Stranger, this club was just as influential as The Crocodile despite its short lifespan. Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture has even made the original circus-inspired entrance arch a permanent addition to their collection. However, 5 years after the closure the original owners were able to resurrect the club as Neumo’s (pronounced New Moe’s) in early 2003. The new club featured an updated sound system and expanded standing room, and still hosts primarily local and indie-rock acts today. RKCNDY Pronounced “Rock Candy,” this iconic club was an all-ages rock haven during the era of the Teen Dance Ordinance, and was featured in our Rainy Day History Podcast for that very reason (Episode 12 - I need the volume higher). The club was prolific, featuring performances from every Seattle band of the 90s, including traveling acts from Radiohead, Joan Jett, Marilyn Manson, and The Verve. Opening in 1991 and closing on Halloween night 1999, this club’s life spanned the length of the Grunge era, inspiring the youth of Seattle to carry the music tradition into the next century. Formerly located south of the Re-Bar by the offramp, there now sits a SpringHill Suites Marriott hotel.

Sources:

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed